Shoop! I wasn’t sure what to expect when my friend Ann and I bought tickets to Sake Seminar and Tasting last night at the Officer’s Club. Would it be comparable to over-priced wine tastings where you wander around filling your glass and sampling dried out cheeses? In fact not. Long tables faced the front where Sake Sommelier Ad Blankestijn, the first non-Japanese sake master (he’s Dutch), gave a three-hour power point presentation to introduce us to sake as a bridge between cultures. I like the idea of sake more than the actual taste, so I wanted to know more. Did you know it takes about two months to brew sake, and then it usually needs to rest about six months? Or that the amino acids in sake suppress the fishy smell of fish where beer or wine would emphasize it? Sake is the 2,000-year-old national drink of Japan and there are now about 1,400 active breweries across Japan. The fact that it’s made from rice links it closely to the cycle of rice cultivation and the associated Shinto fertility rituals, rice-planting ceremonies and harvest celebrations. It’s also an important part of many relationship formalizations, from weddings to the geisha-maiko relationship to joining the yakuza.

Shoop! I wasn’t sure what to expect when my friend Ann and I bought tickets to Sake Seminar and Tasting last night at the Officer’s Club. Would it be comparable to over-priced wine tastings where you wander around filling your glass and sampling dried out cheeses? In fact not. Long tables faced the front where Sake Sommelier Ad Blankestijn, the first non-Japanese sake master (he’s Dutch), gave a three-hour power point presentation to introduce us to sake as a bridge between cultures. I like the idea of sake more than the actual taste, so I wanted to know more. Did you know it takes about two months to brew sake, and then it usually needs to rest about six months? Or that the amino acids in sake suppress the fishy smell of fish where beer or wine would emphasize it? Sake is the 2,000-year-old national drink of Japan and there are now about 1,400 active breweries across Japan. The fact that it’s made from rice links it closely to the cycle of rice cultivation and the associated Shinto fertility rituals, rice-planting ceremonies and harvest celebrations. It’s also an important part of many relationship formalizations, from weddings to the geisha-maiko relationship to joining the yakuza.

So here’s the break down of sake by grade:

So here’s the break down of sake by grade:

Futsu-shu — this is ordinary sake, made with less-refined rice and containing up to two-thirds added alcohol. It has a chalky, minerally taste. This style of sake-making became popular in post-WWII Japan as rice shortages plagued the nation. It was a difficult time and people sought sake not for a tasting or food-pairing experience but for relief from the tragedy and difficulties of life in the devastated economy. Drinking to oblivion remains popular and so does this style of inexpensive “table sake” (about 70 percent of all brewed sake). No need to refrigerate this type of sake, and it’s usually served hot to mask any shortcomings. Lots of added sugar to further cover shortfalls can leave you with a bad headache.

Honjozo — Premium sake with a dry, light, fresh taste. “Premium” means the rice polishing ratio is at least 70 percent. That means the rice has been polished down to 70 percent of the original volume, resulting in a more refined flavor. Honjozo makes up about 11 percent of the market and is ok to be served at any temperature.

Junmai — Premium sake with a full taste. This is pure, authentic sake and should be served at room temperature or lukewarm. Rice can be tasted in this brew, which was the standard sake of Japan until about WWII. Junmai pairs well with many meats and food and makes up less than 10 percent of the sake market.

Ginjo — Aromatic sake where the rice is polished down to 60 percent or less of the original grain. The fruity or floral bouquet varies with the type of koji (cultivated mold that breaks down the starch in rice prior to the addition of yeast) used in brewing and is a good pairing for grilled fish and white meat.

Ginjo — Aromatic sake where the rice is polished down to 60 percent or less of the original grain. The fruity or floral bouquet varies with the type of koji (cultivated mold that breaks down the starch in rice prior to the addition of yeast) used in brewing and is a good pairing for grilled fish and white meat.

Daiginjo — The best of the best, extra aromatic sake, daiginjo makes a good aperitif and should not used as a meal accompaniment. The rice is polished down to 50 percent. Ginjo and Daiginjo are really expensive, should always be consumed cold, and together make up just 7.5 percent of the sake market.

So how the heck are you supposed to use this knowledge when all the labels are in kanji? Easy! Sake labels list alcohol content (which will be less than 20 percent) and the rice polishing ratio (less than 70 percent means premium sake). If the label has a number higher than 20 and lower than 70, you have a fine bottle of sake in your hands.

There are a lot more sake distinctions, including Nigori: a cloudy sake usually enjoyed for the New Year; Muroka: unfiltered sake; Genshu: fiery, raw, undiluted sake served on the rocks in summer; Nama: unpasteurized cold sake popular in the fall; Shiboritate or Shinshu: non-matured, young sake that’s usually pasteurized and pairs well with many Western dishes; Jukuseishu and Koshu: vintage aged (5-20 years) sakes brewed in Kobe and Fukushima with a deeper taste and best as an after-dinner drink; Taruzake: keg sake tasting of Japanese cedar, a nostolgic taste for many Japanese; Kassei-shu: cold, sparkling sake revived in the 1960s from a 1,000-year-old process; Kijoshu: dessert sake similar to port (my favorite!).

Another variation to watch for is kimoto or yamahai sake. This designator means the brewery took an extra two weeks to allow the process to produce its own lactic acid instead of adding it like an ingredient. The result is a deeper, richer taste that makes these premium sakes the perfect accompaniment to creamy sauces, meat, Chinese food and cheese.

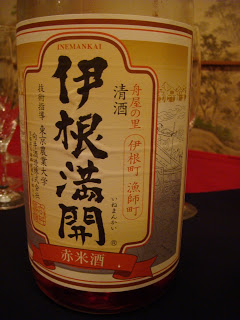

Fun fact: the Japanese invented pasteurization 200 years before Louis Pasteur. We tried eight premium sakes, with food if appropriate. Our first taste was the Ine Mankai, a sweet, sherry-like sake made from a special red rice and therefore falling into none of the above categories. That was one of my favorites. Next we were served yakitori and negi—grilled chicken and Japanese leeks with a accompaniment of Kikuhime Yamahai Junmai Muroka Nama Genshu. Let’s translate that: Kikuhime (sake name) Yamahai (natural lactic acid, extra two-week process) Junmai (premium full-taste sake) Muroka (unfiltered) Nama (unpasteurized) Genshu (fiery undiluted summer sake).

We tried eight premium sakes, with food if appropriate. Our first taste was the Ine Mankai, a sweet, sherry-like sake made from a special red rice and therefore falling into none of the above categories. That was one of my favorites. Next we were served yakitori and negi—grilled chicken and Japanese leeks with a accompaniment of Kikuhime Yamahai Junmai Muroka Nama Genshu. Let’s translate that: Kikuhime (sake name) Yamahai (natural lactic acid, extra two-week process) Junmai (premium full-taste sake) Muroka (unfiltered) Nama (unpasteurized) Genshu (fiery undiluted summer sake).  Then we tried Gozenshu Junmai Shiboritate (translation: full-taste, young, unmatured sake), followed by a sake made with Miyamizu (temple water found to produce very delicious sake) in Kobe. Kobe and Fukushima make a lot of premium sakes because Kobe Port made it easy to ship. Next we had a Suehiro Kira Honjozo—very dry and peppery, good with sushi and sashimi (top picture shows this sake and food pairing, which was in fact tasty), followed by Daishichi Minowamon Junmai Daiginjo (rich-tasting, aromatic vintage sake). I was disappointed with the sparkling Tsuki no Katsura Nakakumi Nigori-zake. I was hoping for something prosecco-ish but got sour beer-ish. Our final pairing was Wakatsuru Kijoshu “port” aged five years and served with vanilla bean ice cream. YUM YUM YUM! I was apparently alone in that opinion though—the other four people at the table liked the sparkling sake and did not enjoy the portly sake.

Then we tried Gozenshu Junmai Shiboritate (translation: full-taste, young, unmatured sake), followed by a sake made with Miyamizu (temple water found to produce very delicious sake) in Kobe. Kobe and Fukushima make a lot of premium sakes because Kobe Port made it easy to ship. Next we had a Suehiro Kira Honjozo—very dry and peppery, good with sushi and sashimi (top picture shows this sake and food pairing, which was in fact tasty), followed by Daishichi Minowamon Junmai Daiginjo (rich-tasting, aromatic vintage sake). I was disappointed with the sparkling Tsuki no Katsura Nakakumi Nigori-zake. I was hoping for something prosecco-ish but got sour beer-ish. Our final pairing was Wakatsuru Kijoshu “port” aged five years and served with vanilla bean ice cream. YUM YUM YUM! I was apparently alone in that opinion though—the other four people at the table liked the sparkling sake and did not enjoy the portly sake. After the seminar we were invited to get second tastes of our favorites. I had another sample of the first red rice sake and finished the evening with the port sake. Kanpai!

After the seminar we were invited to get second tastes of our favorites. I had another sample of the first red rice sake and finished the evening with the port sake. Kanpai!

Roke-Dokey

Roke-Dokey Parenting Advice

Parenting Advice Summer Solstice at the Royal Hawaiian

Summer Solstice at the Royal Hawaiian The Circle of Life

The Circle of Life

Sounds like fun! Nice dress, by the way. 🙂