I ripped tape off the box and sifted through browned envelopes postmarked from the 1930s through the early 1990s–submissions, rejection letters, paystubs collected across six decades of writing. And a yellowed newspaper.

Pay dirt!

Last week I called the library in Quincy, Illinois, and asked them to check the Quincy Herald-Whig newspaper archives for my grandmother’s byline. They couldn’t find her name in the microfilm; only the Associated Press stories used bylines back then, they told me. I’d always known my grandmother studied journalism, but it wasn’t until talking to Grandfather recently that I learned she’d been a staff reporter for several years, even after she got married, until she got pregnant with my dad’s oldest brother.

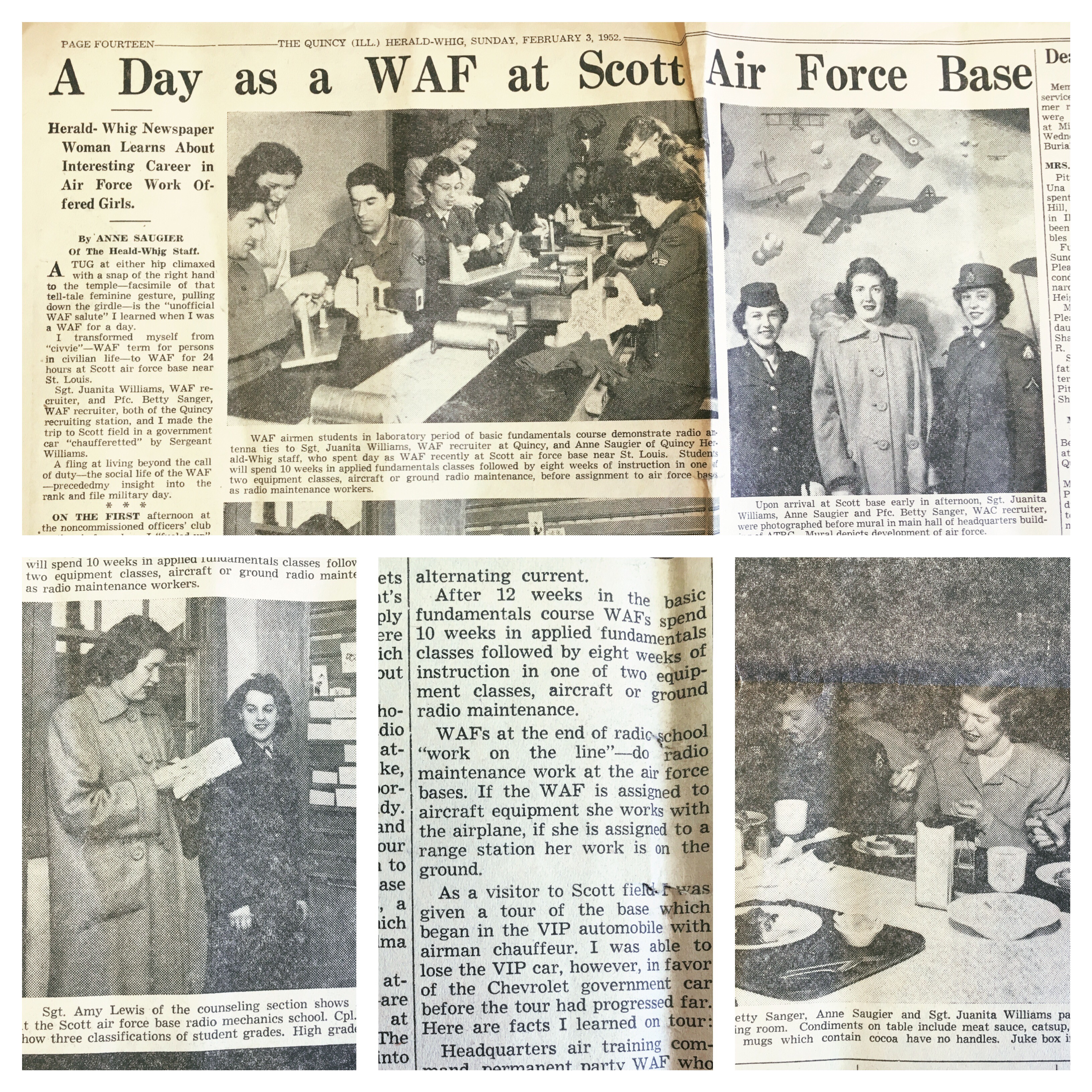

And here in this box of old papers my aunt found was her byline in a 1952 full-page story, “A Day as a WAF at Scotts Air Force Base,” complete with photos OF HER working on the story.

Pure gold.

“Herald-Whig Newspaper Woman Learns About Interesting Career in Air Force Work Offered Girls.”

Her earliest stories were published in a literary newsletter in the late 1930s when she was about 12 (for $1). My first story ran in The Katy Times when I was 14. Seeing the photos of her mid-assignment, her trench coat buttoned to the collar, I had a heady sense of fatalism and finding treasure. OF COURSE I feel compelled to pitch stories and post to Passport Diaries. I can’t help it. It’s in my blood. She continued submitting stories into the 1990s at least, reading from the postmarks in this box. It’s like seeing my future. Hee hee hee, treasure!

Sunday, February 3, 1952

A Day as a WAF at Scott Air Force Base

Herald-Whig Newspaper Woman Learns About Interesting Career in Air Force Work Offered Girls.

By ANNE SAUGIER of the Herald-Whig Staff

A tug at either hip climaxed with a snap of the right hand to the temple—facsimile of that tell-tale feminine gesture, pulling down the girdle—is the “unofficial WAF salute” I learned when I was a WAF for a day. I transformed myself from “civvie”—WAF term for persons in civilian life—to WAF for 24 hours at Scott Air Force Base near St. Louis. Sgt. Juanita Williams, WAF recruiter, and Pfc. Betty Sanger, WAF recruiter, both of the Quincy recruiting station, and I made the trip to Scott field in a government car “chaufferetted” by Sergeant Williams. A fling at living beyond the call of duty—the social life of the WAF—preceded my insight into the rank and file military day.

On the first afternoon at the noncommissioned officers’ club on the Air Force base I “fueled up” with pie and malted milk as noncommissioned officers—those with the stripes on their sleeves—do during free moments throughout the day and evening. Service men and women also turn out en masse to other club-sponsored projects including bingo and dance nights. Between 7 and 8 that night, bingo night at the club, immaculate WAF’s—who a short time before were a flurry of girls standing in line at the ironing board, shining shoes and making tracks to and from the shower—appeared at the club, some in, some out of uniform. Regulations permit the WAF to dress in the new blue uniform or a casual date dress of her own choosing after duty hours. the new trim uniform in medium blue is worn with a light blue blouse with darker blue trim in long or short sleeves. A dressy white blouse with blue trim may be worn by the WAF off duty. This new dress for the girls—an asset to any female—coupled with myriads of airmen per each WAF puts Scott Field in the realm of a woman’s paradise.

WAF meets airman for a movie date or an evening at home in barracks day rooms complete with overstuffed sofas but minus the brat brother demanding a quarter to get himself lost. Refrigerators which contain the makings for icebox raids, television sets and record players for jitterbugs are in day rooms at Scott Field. For the WAF—when she prefers to lounge in pajamas or robe rather than dress in her Sunday go-to-meetin’ togs—there are barracks day rooms “for women only” replete with occasional chairs, coffee tables and television sets. Here, as well as in their rooms, WAFs are a party to the toiletries of milady, most common of which is pinning up the hair while viewing the television screen. Frills—usually in bright hues—designate the barracks rooms as housing units for women. Double rooms, known to WAF as cubicles, have red, yellow, pink, green or blue curtains at the entrance with matching dressing table skirt, bedspread or rugs. The room furnishings, which vary from cubicle to cubicle, depend upon the ingenuity of the WAF occupant. They fashion the dressing tables from a small table which extends from the base of the window. The bedspreads disguise single army beds. Shag rugs cover spotless floors.

It is the responsibility of the girls to keep their own rooms clean. The halls, latrines (WAF bathrooms) and the day room are also kept clean by the WAF. A schedule of these special details (duties) appears on the bulletin board in the hall to show each WAF her time to clean. In the morning I awoke, not to the blare of a bugle blowing reveille as was my preconceived notion of rise and shine in the service, but to the sweet notes of a radio alarm clock, the possession of my roommate. I followed WAFs methodically making their way to the latrine, bushed my teeth and washed my face with borrowed soap since I had forgotten my bar and was dressed in time to get inside Mess 7 before the doors closed at 7:30. By now I was wide enough awake to see the “dead soldier’s meal”—a sample of this morning’s breakfast fare enclosed in a glass case—and knew that I could fill my tray with pancakes, sausage, orange juice, milk, cereal, toast and coffee in the cafeteria line. Coffee is served most practically in thick mugs without handles which cool the coffee to the drinking point and insulate it to that temperature.

Pillowcase, pillow, two sheets and two army blankets which had given me a good night’s sleep were turned into the supply room after breakfast. Here WAFs bring their laundry, which is ready for pick-up after about a week. A half hour later when a photographer and I went to radio school, WAFs and airmen who attended classes jointly, student-like, availed themselves of the opportunity for a time out from study. To the credit of the WAFs and airmen, prior to their notice of our presence, they were at attention to the lecturer rather than at ease nodding heads over notebooks, a half conscious condition with which I became acquainted at my alma mater. Classes—the ones which we attended began at 6a.m.—are taught in three shifts ending at noon, 6p.m. and midnight. The class period is divided equally into laboratory and classroom work. I was in classes with students in their 12th week of the radio mechanics fundamentals course. in the laboratory I learned how to make aircraft antenna ties. Each student builds a radio receiver during the 12 weeks in basic fundamentals laboratory period.

In the classroom I learned about the theory of radio. Students begin with the study of direct and alternating current. After 12 weeks in the basic fundamentals course WAFs spend 10 weeks in applied fundamentals classes followed by eight weeks of instruction in one of two equipment classes, aircraft or ground radio maintenance. WAFs at the end of radio school “work on the line”—do radio maintenance work at the air force bases. If the WAF is assigned to aircraft equipment she works with the airplane, if she is assigned to a range station her work is on the ground. As a visitor to Scott Field I was given a tour of the base which began in the VIP automobile with airman chauffeur. I was able to lose the VIP car, however, in favor of the Chevrolet government car before the tour had progressed far. Here are facts I learned on tour:

Headquarters air training command, permanent party WAF who have been stationed at Scott Field since July, 1951, as office workers and control tower instructors and operators, occupy the cubicles. At present about 25 WAFs are members of headquarters air training command but the number soon will be doubled. The remainder of the WAFs at Scott Field Air Force Base, numbering 305, are members of the student squadron. Two hundred of these WAF also are permanent party. The remaining 105 are students in radio. Student WAFs at present are housed in open bay—large barracks without partitions. Plans are under way to convert the student barracks to cubicles.

My day at Scott Field was not the first knowledge of women in service. My sister, WAC Cpl. Barbara Kerr of New Salem, is stationed in Heidelberg, Germany.

Noon news daily 12 to 12:30 WGEM.

Mussels in Brussels

Mussels in Brussels Shinsaikaibashi Bridge

Shinsaikaibashi Bridge Easter Sunrise

Easter Sunrise I Don’t Like It Park!

I Don’t Like It Park!